If "it takes a village", then isn't polyamory ideal? Yet people will attack it on the grounds that it's "bad for the children." When it comes to polyfidelity at least, this is not the case at all. Having multiple sources of support can contribute to upward mobility,

as this man attests:

“Polyamory equals privilege.” It’s a sentiment I’m hearing more and

more often. As the story goes, the average single working parent with a

low-wage job has no time to go out on dinner dates, attend epic

debaucherous parties, and engage in various leisure activities with

their many lovers.

[...] This viewpoint seems to be gaining traction, maybe even reaching

dominance, as nonmonogamy becomes more visible. It’s buoyed in no small

part by media portrayals like Showtime’s intensely Caucasian Polyamory: Married and Dating,

a veritable festival of hot tubs, champagne, and $300 yoga pants. Or

the fact that, at least online, the poly community is mostly white and highly educated.

|

| Is this how polyamory looks? |

It’s easy to see why people might come to think of polyamory, at least in the form they see today, as the purview of “rich, pretty people with too much time on their hands.” However,

this viewpoint fails to acknowledge the underprivileged nonmonogamists

among us — it serves to alienate the disadvantaged, to discourage them

from even trying it. This denies polyamory’s considerable economic,

social, and structural benefits to those who need them the most.

[...] I am a second-generation poly person, who grew up in the eighties. My

parents were quite poor when I was born, and I’ve experienced a great

deal of class mobility over the course of my life. I’ve witnessed

first-hand how economic privilege is not a requirement for nonmonogamy.

In fact, the nontraditional nature of my family directly facilitated my

own escape from a life of poverty. This is what it was like for me,

growing up poor in America with two moms and a dad.

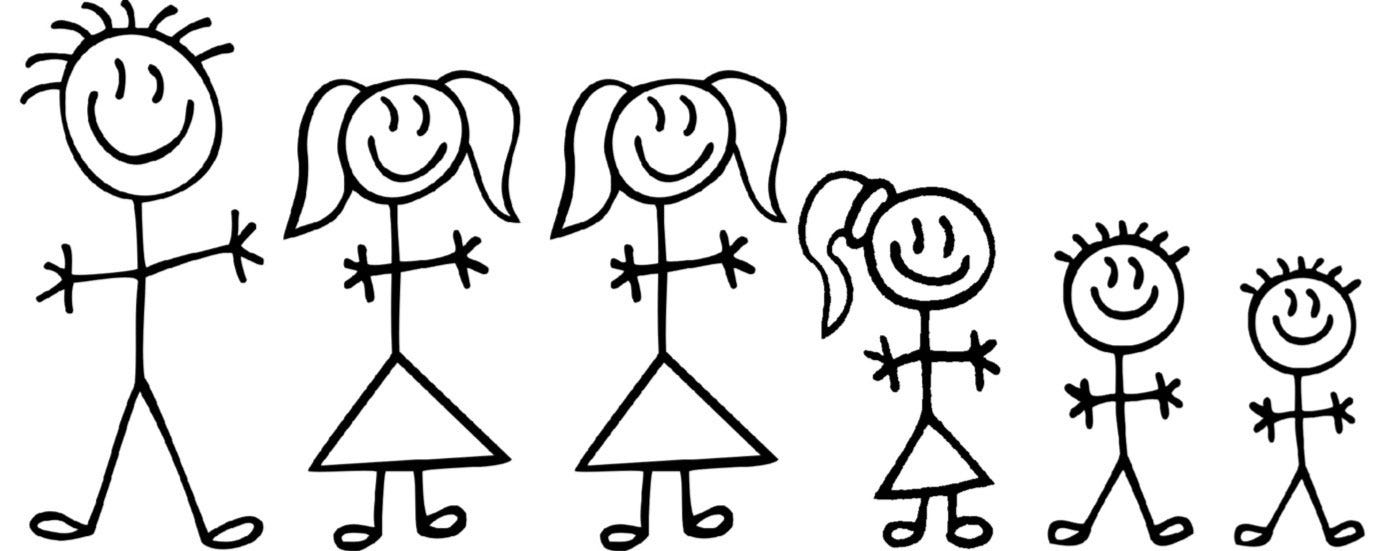

|

| My old house. |

[...] My biological mother’s family were immigrant farmers who fled postwar

Eastern Europe for the Midwest. She had attended some community

college, but left school and moved to California in her early twenties.

My mom had a dizzying array of entry-level jobs, from veterinary

assistant to school bus driver. Some of my earliest memories are of

standing with her for hours in the food stamp line in the town Veteran’s

Hall, and the giant bricks of mild yellow cheese we’d get from WIC.

My “other” mom, who as a small child I knew simply by her

first name, was also a farm girl. Her parents were devout Jehovah’s

Witnesses. Their family’s interpretation of the Scripture prohibited

them from allowing her to receive an education. When she met my parents

around the time I was born, she had a 3-year old daughter from a

previous, abusive, marriage, and was working as a minimum-wage retail

clerk. She taught me to read in the year before kindergarten.

My father’s mother was a widow, disowned by her family for

refusing to abandon a son with an intellectual disability. That same

son, my uncle, regularly abused my dad throughout his childhood and

adolescence. To escape his home life, my father joined a gang, which

kept him out of school, and led him into alcoholism and methamphetamine

addiction. He’s also an incredible surrealist painter. I believe that

his focus on art, coupled with his relationship with my mother, led him

through this long, hard phase of his life. By the time I was born he had

recovered from his addictions, but a host of complex medical issues

left him disabled, on a meager fixed income from SSI. He played a mean

game of pool, though, and would win local bar tournaments each winter so

that we could have Christmas presents.

We lived my entire childhood in a tiny shack in the Northern

California forest with only a wood stove for heat. [...] I learned to

live cheap by reusing and repairing everything. I’d hold the flashlight

while my dad, covered in grease, fixed our decrepit pickup truck. When

it was broken anyway we would bike miles down the highway, backpacks

full of groceries. At night, my mom would sit and watch TV while darning

socks stretched over a burned-out lightbulb.

[...] My parents all slept together in one big bed, on a pair of twin

mattresses pushed together. My dad would complain about falling into the

space between them, but it was what we could afford.

Things are very different for me now. After many years as a

successful software developer, I’m the founder of my own company, and

have made my home in the heart of one of the world’s most expensive

cities. My friends and I maintain a spacious workshop for building

large-scale tech art, and I curate a growing collection of passport

stamps. [...] I’m very lucky: my parents are remarkable people who care

deeply for me and did an admirable job of raising me. But, it certainly

didn’t hurt that there were three of them.

[...] If privilege can be defined as unearned advantage, then for my family

polyamory was not the result of privilege. Rather, it was a source of

it. I can see now that my parents’ triad provided them with the

resources and mutual support they needed to be so conscientious in

raising me and my two siblings. It freed them from many of the difficult

decisions a poor, working family often has to make: attend the PTA

meeting, or put in some overtime? Actively raise the children, or make

enough money to feed them? A three parent household has 50% more time,

income, and experience than a two-parent household. That counts for a

great deal.

[...] Had my own parents been monogamous, perhaps I’d have learned

to read a year or two later, denying me some of the academic advantage I

enjoyed for the entirety of my education. Maybe they would not have

been able to afford that obsolete computer they bought when I was a kid,

or the time to learn and then teach me Atari BASIC, which became the

foundation of my career (yes, I’m one of those insufferable geeks who

started programming when I was 8). Maybe when our house flooded in 1986, we’d have been left homeless,

without the resources to rebuild. These are a few clear examples, but

there’s a thousand other tiny things, from breastfeeding to bedtime

stories, that confer advantage to the children of parents with spare

time and extra cash.

Growing up, I was surrounded by the wreckage of relationships

destroyed by infidelity and divorce. Custody battles were a fixture of

my young existence, and I witnessed the toll they took on my friends’

lives. This experience is not unique: 57% of impoverished families in

America have a single parent. While I’ll be the first to admit that

relationships are complicated, I can’t help but wonder how those

families might have been different had the parents been skilled in

responsible nonmonogamy. If American culture valued a relationship’s

ability to change without ending, if we ascribed different meaning to

sexual fidelity, could some of those kids have retained a mom or a dad?

If we were better at recognizing our own ability to find love, sex, and a

co-parent in separate individuals, could those families have been

stronger?

[...] There is an earnest effort here to acknowledge a group’s humanity by

being sympathetic to their struggle. Yet, we cast the poor as cardboard

characters. Work, sleep, feed the kids, repeat. It’s just not like that.

Poverty is complicated. Discussions of privilege seek to promote

understanding, but overly reductive models can be marginalizing. They

deepen our class divide.

[...] There is room in most people’s lives for polyamory. It can even play a

significant role in helping to alleviate poverty, but it’s not a

magical solution. Not everybody is interested in nonmonogamy. It makes

dating easier in some ways and much harder in others. For the poor

especially, there are unique challenges brought on by the clash between

alternative sexuality and culture, religion, or prevailing community

values. In some places, the intersectional oppression that poor poly

people face might tip the scales: the community lost could be of greater

value than the community gained.

My family certainly had its trials. Cohabitation is hard, and a

three-person relationship is a tricky thing to manage. We were also, no

doubt, subject to considerable bigotry, especially back in the

eighties. As a child I was largely insulated from it. Still, from my

perspective it was entirely worth it. When I ask my parents, they have

no regrets.

No comments:

Post a Comment